Oh my gosh. the system actually works and those that decided to make it work are in the cross hairs of the unbelievers. Old habits are hard to break for those taking the assistance and for those that can't or won't understand how the system of welfare cripples the human spirit.

As the saying goes, 'you can't steal for home if you are afraid to leave first base.'

How Maine’s Time Limit on Welfare Pushed One Woman to Pull Herself Out of Poverty

Melissa Quinn / @MelissaQuinn97 /

Rothrock knows the moment she hit rock bottom. It was 2007, and Rothrock went into the pharmacy in Bucksport, Maine, to pick up a prescription for Vicodin that she had called in herself. Her two daughters were in the car, and after she had picked up the pills, Rothrock got back into a car she was renting and began to drive away. But agents with the Drug Enforcement Administration pulled up behind her, and at that moment, one word entered Rothrock’s mind. “Finally.”

Rothrock, now 44, had been battling addiction for more than 20 years. After she was arrested in 2007, Rothrock cleaned up and enrolled in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, or TANF, and worked to find a full-time job.

Now, nearly a decade later, she’s transitioned off of public assistance and has a full-time job working for the state, a change she attributes in part to the 60-month time limit enacted by Maine Gov. Paul LePage, a Republican, in 2012. “It forced me to do what I had to do to get off benefits and start making my own money again,” she told The Daily Signal.

‘It’s About Time’

Rothrock’s battle with drugs and alcohol began when she was just 12 years old, when Rothrock, who was living in New Jersey with her family, and her friends had the run of a friend’s house. The friend’s parents owned a golf course and were never home, Rothrock recalled, and even less so since they were going through a divorce.

At first, it started with liquor and then moved on to pot, she told The Daily Signal. Later, as Rothrock progressed through her high school years, her grades dropping from As to Cs and Ds, she began to get into harder drugs: cocaine and painkillers—Vicodin, specifically—after a dentist prescribed Rothrock medicine after having dental work done. “I was trying to get out of my reality,” she said. “The painkillers helped me achieve that. I spent the next I don’t know how many years looking for painkillers, and I came up with any excuse to get them.”

Rothrock had the connections to get the drugs she needed in New Jersey. But when she was 29 years old, her dad retired from the same job he’d worked in for 33 years and decided to make Maine, their then vacation spot, a permanent residence for him and Rothrock’s mother.

At first, Rothrock stayed in New Jersey, but then decided to move to Maine herself.

There, she was forced to find new connections, and in Maine, Rothrock said, “everybody knows everybody,” so she wasn’t having much luck. So Rothrock became creative.

She started calling in prescriptions for herself and calling them into the same pharmacy consistently.

Eventually, the pharmacy took notice, and that’s when the DEA went calling. “It’s about time,” Rothrock remembered thinking.

A Security Blanket

Rothrock faced three felony charges after getting arrested. She was able to attend drug court, which provides community-based treatment service to people with substance abuse, and graduated, dropping her charges from felonies to misdemeanors.

While using, Rothrock managed to hold down a steady job at AT&T, which she continued after moving to Maine in 2001. But after her first daughter was born—and before being arrested in 2007—Rothrock quit her job. The next three years, from 2004 to 2007, she said were the worst of her life.

The day Rothrock was arrested was the first day of her sobriety, she said, and September marks nine years since she’s touched drugs or alcohol. But by 2007, Rothrock had two daughters and no steady full-time employment, so she began receiving benefits from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

TANF is a program that provides financial assistance to needy families and trains them for employment. To receive benefits, recipients must work, volunteer, attend school or vocational training, or actively be looking for a job.

Rothrock, newly clean and sober for the first time since she was a teenager, complied with the rules of the program and received TANF consistently for more than four years, working part-time for spans of time and receiving unemployment for others. But in 2011, the newly elected LePage and his administration reinstated a 60-month lifetime limit on TANF eligibility, and Rothrock was quickly approaching the end of her five years.

“When you’re on TANF and you’re getting that money, it becomes your security blanket,” Rothrock said. “It seems like a heck of a lot more money than it really is because that’s the only money you’re getting. To go off of it was, it was really scary.” “It came down to the wire,” she continued. “I knew my TANF was closing, and I had to secure a job or I would have no income.”

Welfare Reform Gets Personal

For LePage, reforming the state’s welfare system was personal. One of 18 children, LePage grew up in poverty in Lewiston, Maine. He was homeless during parts of his teenage years, and according to the Portland Press Herald, LePage ran away from home when he was just 11 years old. When he was young, LePage worked odd jobs when he wasn’t at school, delivering groceries and gathering empty glass bottles for the driver of a Pepsi-Cola truck he met.

So when he ran for governor in 2010, LePage made welfare reform a centerpiece of his platform.

“I was born into this,” he told The Daily Signal. “I understand it. I come from a family of 18 kids. I watched it my whole life. A few of us got up, and a few of preferred to wait for the check. We’ve been in a war against poverty since 1954, and it’s failed miserably.”

In the 2011 budget released his first year in office, LePage reinstated a five-year lifetime cap on eligibility for the TANF program, which serves needy families, but allows recipients to qualify for exemptions from a list of eight. “If you don’t have a time limit, all the education in the world isn’t going to be very good. You give them a time limit and then you encourage them and inspire them to seek the education,” LePage said of his change to the TANF program. “My feeling was, you’ve got five years. We’re going to work with you starting today, and in five years, you won’t need the assistance because you’re going to be self-sufficient. And that’s the whole purpose.”

The government created the TANF program through the Personal Responsibility and Opportunity Act, which President Bill Clinton signed into law in 1996. The law originally imposed a 60-month lifetime limit on eligibility, but some states like Maine had waived it for years.

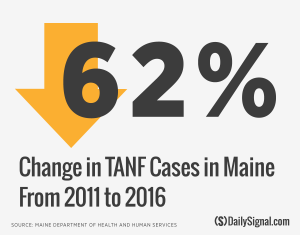

Since LePage and the state legislature reinstated the time limit, which took effect in 2012, the number of cases in the state declined 62 percent from 2011 to 2016, according to the Maine Department of Health and Human Services.

According to a 2014 study from the University of Maine, 36 percent of TANF households received exemptions. “Front and center to the governor’s reforms has been promoting employment, that a job is not a dirty word. A job is what contributes to self esteem, to self worth, to human dignity, and to really change someone’s life, we need to get them on that pathway to prosperity and out of poverty through a job,” Mary Mayhew, commissioner of the Department of Health and Human Services, told The Daily Signal in an interview last month.

“I think for any of us, we can appreciate if there is no time limit, if there is no goal, if there is no consequence, we’re not going to do what needs to be done,” she continued.

After reinstating a time limit for the TANF, LePage and his administration moved to restoring a work requirement for able-bodied adults without dependents through the food stamp program.

The 1996 welfare reform law required childless adults between the ages of 18 and 49 to either work at least 20 hours per week, volunteer one hour per day or participate in a vocational training program to receive food stamp benefits. But states could request waivers from the work requirement if it had high unemployment or job shortages.

Maine waived work requirements since 2008. But in July 2014, LePage and Mayhew’s Department of Health and Human Services decided it would no longer do so. “I think it’s important for everyone to keep in mind if you are on these programs, it means you are living in poverty,” Mayhew said. “We should absolutely refuse to accept that that is the way of life that should be accepted for these individuals, that we actually believe in their potential. So we began to look at some of the policies, or worse, the waivers that Maine had pursued.”

In Maine, nearly 12,000 food stamp recipients were considered able-bodied adults without dependents under federal law, according to the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, and received roughly $15 million in food stamp benefits each year.

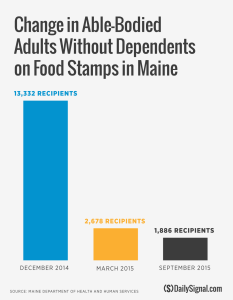

After implementing the work requirements for childless adults, the number of food stamp recipients dropped from 13,332 in December 2014 to 2,678 in March 2015, an 80 percent decline. By September 2015, the number of childless adults on food stamps dropped further to 1,886.

Additionally, the state reported that incomes for able-bodied adults without dependents who left the food stamp program increased 114 percent.

“The goal is not going to eliminate everyone on welfare. Not everyone on welfare is going to be eliminated. You have people with intellectual disabilities. You have people with physical disabilities, and we all grow old. Many of those folks are going to continue, we have services that they’re going to need, and we need to have a good safety net and make sure we take care of those folks,” LePage said.

“The issue is those that are able-bodied that have no mental or physical disabilities,” he continued. “We want to try to give them the skill set they need to keep a good job and advance themselves and their families, and to achieve the American dream.”

A Contentious Debate

Tackling welfare reform has not been easy for LePage and Mayhew, who have both been criticized for hurting rather than helping those in poverty after implementing a time limit for TANF eligibility and work requirements for childless adults.

While the state Department of Health and Human Services has pointed to the drop in caseloads in both TANF and the food stamp program as measures of success, Maine Equal Justice Partners, a nonprofit that focuses on poverty, disagrees. “A drop in the caseload is no measure, especially when you don’t know what’s happened to those folks,” Chris Hastedt, the group’s public policy director, told The Daily Signal. “We see many people who leave TANF who are not equipped and able to support their families. That has to do not just with education, but also with various levels of disability that make it more difficult for them to become employed and stay employed.”

Maine Equal Justice Partners, with the University of Maine, conducted a study on what happened to 13 families who left TANF after 60 months following LePage’s reforms. According to the study, 31 percent of the 13 interviewed were employed or had a member of their household who was employed after losing their TANF benefits, an increase of 7 percentage points. But more than half of the families surveyed didn’t include an employed adult.

“It doesn’t stop when people leave TANF. We often see people even within the five-year window coming back and forth because the kinds of employment we’re creating in this country these days isn’t the most sustainable. It’s part-time,” Hastedt said. “The irregularity of hours for single parents to try to balance when you don’t know until you get in that day whether you’re working or not—that’s hard stuff for people to rely on to stabilize themselves and their families.” Additionally, nearly one-third of the families in the study lost their houses after their TANF eligibility ended.

“People need a benefit level that will enable them not to live in stress and depression and fear and just what it feels like every day to wake up living at that level of poverty, which makes it very difficult to move forward,” Hastedt said. “I think it’s stabilizing families. The whole program needs to be more individualized.”

If there is one point that both Hastedt and LePage agree on, though, it’s the role that education plays in lifting people out of poverty.

“There’s not a one-size-fits-all for everyone, but I think we all know that education is an equalizer and an important asset in people’s lives,” Hastedt said.

Meanwhile, LePage himself says that his life began when he arrived at Husson College in Bangor, but contends that limits still need to be implemented and enforced. “Go roll up your sleeves and go find out what poverty is all about,” he said. “Once you understand what it’s all about, the answer comes to you very quickly. It’s all about education. You don’t have to be around it for 50 years to realize that once people learn skills, they never lose them. They are theirs to keep. It’s the old saying, you can buy somebody lunch or you can take them out and teach them to fish.”

Moving Forward

Knowing she was nearing the end of her eligibility for the TANF program, Rothrock began working with state workers through Maine’s TANF-ASPIRE, or Additional Support for People in Retraining and Employment, program. All TANF recipients are required to go through the ASPIRE program, which provides assistance with job searches, training, and education to those on welfare.

Through the ASPIRE program, Rothrock began working 30 hours per week at a nonprofit.

“I got in there, and that’s when everything started to come back,” she said, “my work ethic and how much I loved working.” She was also paired with a mentor who, along with ASPIRE employees, encouraged her to apply for a job with the state Department of Health and Human Services. Rothrock did, and was hired in 2012 as a clerk in the department that oversees eligibility of those in TANF.

At first, she would support the state’s eligibility specialists, answering phones, pulling files, and opening and sending mail. But in the years since, she received raises and a promotion. In 2014, Rothrock was promoted in the eligibility department and now works on discrepancy reports the state receives from the Department of Labor and Social Security Administration. “Once the money starts coming in, it’s the best feeling in the world,” Rothrock said. “My confidence started to come back.”

Though Rothrock was no longer eligible for TANF, the state continued to provide her with transitional benefits, including childcare and supplemental food stamps. The state also reimburses those who leave TANF for mileage to and from their job. Rothrock admits that she was scared to “go back into the real work” and eventually go off public assistance all together. But she also observed what she said is a “generational” cycle of poverty for those on TANF.

“Nothing feels as good as earning your own money, and it’s scary to not have that safety net there,” she said. “I see these girls whose mothers are on TANF. It’s handed down. It’s a way of life. You turn 18. You get pregnant. You come to [the Department of Health and Human Services] and get on benefits.”

In April 2015, LePage and state Senate President Mike Thibodeau, a Republican, unveiled a bill further reforming TANF. Rothrock was on hand during a press conference detailing the legislation and spoke about her transition from public assistance to independence. Though LePage has faced resistance from Democrats in his state for his reforms, he’s continued to move forward and is now shifting his focus from TANF to further reforming the food stamp program.

“I’ve been the luckiest man on earth. I went from homelessness to governor of the state of Maine, and it’s my turn to give back, and it’s my way of trying to teach people how I did it,” LePage said. “For those who say it’s going to create poverty and hardship, let me tell you something. You don’t want to be poor. If you’re poor and you have the skills to get out, you will get out.”

As the saying goes, 'you can't steal for home if you are afraid to leave first base.'

How Maine’s Time Limit on Welfare Pushed One Woman to Pull Herself Out of Poverty

Melissa Quinn / @MelissaQuinn97 /

Rothrock knows the moment she hit rock bottom. It was 2007, and Rothrock went into the pharmacy in Bucksport, Maine, to pick up a prescription for Vicodin that she had called in herself. Her two daughters were in the car, and after she had picked up the pills, Rothrock got back into a car she was renting and began to drive away. But agents with the Drug Enforcement Administration pulled up behind her, and at that moment, one word entered Rothrock’s mind. “Finally.”

Rothrock, now 44, had been battling addiction for more than 20 years. After she was arrested in 2007, Rothrock cleaned up and enrolled in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, or TANF, and worked to find a full-time job.

Now, nearly a decade later, she’s transitioned off of public assistance and has a full-time job working for the state, a change she attributes in part to the 60-month time limit enacted by Maine Gov. Paul LePage, a Republican, in 2012. “It forced me to do what I had to do to get off benefits and start making my own money again,” she told The Daily Signal.

‘It’s About Time’

Rothrock’s battle with drugs and alcohol began when she was just 12 years old, when Rothrock, who was living in New Jersey with her family, and her friends had the run of a friend’s house. The friend’s parents owned a golf course and were never home, Rothrock recalled, and even less so since they were going through a divorce.

At first, it started with liquor and then moved on to pot, she told The Daily Signal. Later, as Rothrock progressed through her high school years, her grades dropping from As to Cs and Ds, she began to get into harder drugs: cocaine and painkillers—Vicodin, specifically—after a dentist prescribed Rothrock medicine after having dental work done. “I was trying to get out of my reality,” she said. “The painkillers helped me achieve that. I spent the next I don’t know how many years looking for painkillers, and I came up with any excuse to get them.”

Rothrock had the connections to get the drugs she needed in New Jersey. But when she was 29 years old, her dad retired from the same job he’d worked in for 33 years and decided to make Maine, their then vacation spot, a permanent residence for him and Rothrock’s mother.

At first, Rothrock stayed in New Jersey, but then decided to move to Maine herself.

There, she was forced to find new connections, and in Maine, Rothrock said, “everybody knows everybody,” so she wasn’t having much luck. So Rothrock became creative.

She started calling in prescriptions for herself and calling them into the same pharmacy consistently.

Eventually, the pharmacy took notice, and that’s when the DEA went calling. “It’s about time,” Rothrock remembered thinking.

A Security Blanket

Rothrock faced three felony charges after getting arrested. She was able to attend drug court, which provides community-based treatment service to people with substance abuse, and graduated, dropping her charges from felonies to misdemeanors.

While using, Rothrock managed to hold down a steady job at AT&T, which she continued after moving to Maine in 2001. But after her first daughter was born—and before being arrested in 2007—Rothrock quit her job. The next three years, from 2004 to 2007, she said were the worst of her life.

The day Rothrock was arrested was the first day of her sobriety, she said, and September marks nine years since she’s touched drugs or alcohol. But by 2007, Rothrock had two daughters and no steady full-time employment, so she began receiving benefits from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

TANF is a program that provides financial assistance to needy families and trains them for employment. To receive benefits, recipients must work, volunteer, attend school or vocational training, or actively be looking for a job.

Rothrock, newly clean and sober for the first time since she was a teenager, complied with the rules of the program and received TANF consistently for more than four years, working part-time for spans of time and receiving unemployment for others. But in 2011, the newly elected LePage and his administration reinstated a 60-month lifetime limit on TANF eligibility, and Rothrock was quickly approaching the end of her five years.

“When you’re on TANF and you’re getting that money, it becomes your security blanket,” Rothrock said. “It seems like a heck of a lot more money than it really is because that’s the only money you’re getting. To go off of it was, it was really scary.” “It came down to the wire,” she continued. “I knew my TANF was closing, and I had to secure a job or I would have no income.”

Welfare Reform Gets Personal

For LePage, reforming the state’s welfare system was personal. One of 18 children, LePage grew up in poverty in Lewiston, Maine. He was homeless during parts of his teenage years, and according to the Portland Press Herald, LePage ran away from home when he was just 11 years old. When he was young, LePage worked odd jobs when he wasn’t at school, delivering groceries and gathering empty glass bottles for the driver of a Pepsi-Cola truck he met.

So when he ran for governor in 2010, LePage made welfare reform a centerpiece of his platform.

“I was born into this,” he told The Daily Signal. “I understand it. I come from a family of 18 kids. I watched it my whole life. A few of us got up, and a few of preferred to wait for the check. We’ve been in a war against poverty since 1954, and it’s failed miserably.”

In the 2011 budget released his first year in office, LePage reinstated a five-year lifetime cap on eligibility for the TANF program, which serves needy families, but allows recipients to qualify for exemptions from a list of eight. “If you don’t have a time limit, all the education in the world isn’t going to be very good. You give them a time limit and then you encourage them and inspire them to seek the education,” LePage said of his change to the TANF program. “My feeling was, you’ve got five years. We’re going to work with you starting today, and in five years, you won’t need the assistance because you’re going to be self-sufficient. And that’s the whole purpose.”

The government created the TANF program through the Personal Responsibility and Opportunity Act, which President Bill Clinton signed into law in 1996. The law originally imposed a 60-month lifetime limit on eligibility, but some states like Maine had waived it for years.

Since LePage and the state legislature reinstated the time limit, which took effect in 2012, the number of cases in the state declined 62 percent from 2011 to 2016, according to the Maine Department of Health and Human Services.

According to a 2014 study from the University of Maine, 36 percent of TANF households received exemptions. “Front and center to the governor’s reforms has been promoting employment, that a job is not a dirty word. A job is what contributes to self esteem, to self worth, to human dignity, and to really change someone’s life, we need to get them on that pathway to prosperity and out of poverty through a job,” Mary Mayhew, commissioner of the Department of Health and Human Services, told The Daily Signal in an interview last month.

“I think for any of us, we can appreciate if there is no time limit, if there is no goal, if there is no consequence, we’re not going to do what needs to be done,” she continued.

After reinstating a time limit for the TANF, LePage and his administration moved to restoring a work requirement for able-bodied adults without dependents through the food stamp program.

The 1996 welfare reform law required childless adults between the ages of 18 and 49 to either work at least 20 hours per week, volunteer one hour per day or participate in a vocational training program to receive food stamp benefits. But states could request waivers from the work requirement if it had high unemployment or job shortages.

Maine waived work requirements since 2008. But in July 2014, LePage and Mayhew’s Department of Health and Human Services decided it would no longer do so. “I think it’s important for everyone to keep in mind if you are on these programs, it means you are living in poverty,” Mayhew said. “We should absolutely refuse to accept that that is the way of life that should be accepted for these individuals, that we actually believe in their potential. So we began to look at some of the policies, or worse, the waivers that Maine had pursued.”

In Maine, nearly 12,000 food stamp recipients were considered able-bodied adults without dependents under federal law, according to the Maine Department of Health and Human Services, and received roughly $15 million in food stamp benefits each year.

After implementing the work requirements for childless adults, the number of food stamp recipients dropped from 13,332 in December 2014 to 2,678 in March 2015, an 80 percent decline. By September 2015, the number of childless adults on food stamps dropped further to 1,886.

Additionally, the state reported that incomes for able-bodied adults without dependents who left the food stamp program increased 114 percent.

“The goal is not going to eliminate everyone on welfare. Not everyone on welfare is going to be eliminated. You have people with intellectual disabilities. You have people with physical disabilities, and we all grow old. Many of those folks are going to continue, we have services that they’re going to need, and we need to have a good safety net and make sure we take care of those folks,” LePage said.

“The issue is those that are able-bodied that have no mental or physical disabilities,” he continued. “We want to try to give them the skill set they need to keep a good job and advance themselves and their families, and to achieve the American dream.”

A Contentious Debate

Tackling welfare reform has not been easy for LePage and Mayhew, who have both been criticized for hurting rather than helping those in poverty after implementing a time limit for TANF eligibility and work requirements for childless adults.

While the state Department of Health and Human Services has pointed to the drop in caseloads in both TANF and the food stamp program as measures of success, Maine Equal Justice Partners, a nonprofit that focuses on poverty, disagrees. “A drop in the caseload is no measure, especially when you don’t know what’s happened to those folks,” Chris Hastedt, the group’s public policy director, told The Daily Signal. “We see many people who leave TANF who are not equipped and able to support their families. That has to do not just with education, but also with various levels of disability that make it more difficult for them to become employed and stay employed.”

Maine Equal Justice Partners, with the University of Maine, conducted a study on what happened to 13 families who left TANF after 60 months following LePage’s reforms. According to the study, 31 percent of the 13 interviewed were employed or had a member of their household who was employed after losing their TANF benefits, an increase of 7 percentage points. But more than half of the families surveyed didn’t include an employed adult.

“It doesn’t stop when people leave TANF. We often see people even within the five-year window coming back and forth because the kinds of employment we’re creating in this country these days isn’t the most sustainable. It’s part-time,” Hastedt said. “The irregularity of hours for single parents to try to balance when you don’t know until you get in that day whether you’re working or not—that’s hard stuff for people to rely on to stabilize themselves and their families.” Additionally, nearly one-third of the families in the study lost their houses after their TANF eligibility ended.

“People need a benefit level that will enable them not to live in stress and depression and fear and just what it feels like every day to wake up living at that level of poverty, which makes it very difficult to move forward,” Hastedt said. “I think it’s stabilizing families. The whole program needs to be more individualized.”

If there is one point that both Hastedt and LePage agree on, though, it’s the role that education plays in lifting people out of poverty.

“There’s not a one-size-fits-all for everyone, but I think we all know that education is an equalizer and an important asset in people’s lives,” Hastedt said.

Meanwhile, LePage himself says that his life began when he arrived at Husson College in Bangor, but contends that limits still need to be implemented and enforced. “Go roll up your sleeves and go find out what poverty is all about,” he said. “Once you understand what it’s all about, the answer comes to you very quickly. It’s all about education. You don’t have to be around it for 50 years to realize that once people learn skills, they never lose them. They are theirs to keep. It’s the old saying, you can buy somebody lunch or you can take them out and teach them to fish.”

Moving Forward

Knowing she was nearing the end of her eligibility for the TANF program, Rothrock began working with state workers through Maine’s TANF-ASPIRE, or Additional Support for People in Retraining and Employment, program. All TANF recipients are required to go through the ASPIRE program, which provides assistance with job searches, training, and education to those on welfare.

Through the ASPIRE program, Rothrock began working 30 hours per week at a nonprofit.

“I got in there, and that’s when everything started to come back,” she said, “my work ethic and how much I loved working.” She was also paired with a mentor who, along with ASPIRE employees, encouraged her to apply for a job with the state Department of Health and Human Services. Rothrock did, and was hired in 2012 as a clerk in the department that oversees eligibility of those in TANF.

At first, she would support the state’s eligibility specialists, answering phones, pulling files, and opening and sending mail. But in the years since, she received raises and a promotion. In 2014, Rothrock was promoted in the eligibility department and now works on discrepancy reports the state receives from the Department of Labor and Social Security Administration. “Once the money starts coming in, it’s the best feeling in the world,” Rothrock said. “My confidence started to come back.”

Though Rothrock was no longer eligible for TANF, the state continued to provide her with transitional benefits, including childcare and supplemental food stamps. The state also reimburses those who leave TANF for mileage to and from their job. Rothrock admits that she was scared to “go back into the real work” and eventually go off public assistance all together. But she also observed what she said is a “generational” cycle of poverty for those on TANF.

“Nothing feels as good as earning your own money, and it’s scary to not have that safety net there,” she said. “I see these girls whose mothers are on TANF. It’s handed down. It’s a way of life. You turn 18. You get pregnant. You come to [the Department of Health and Human Services] and get on benefits.”

In April 2015, LePage and state Senate President Mike Thibodeau, a Republican, unveiled a bill further reforming TANF. Rothrock was on hand during a press conference detailing the legislation and spoke about her transition from public assistance to independence. Though LePage has faced resistance from Democrats in his state for his reforms, he’s continued to move forward and is now shifting his focus from TANF to further reforming the food stamp program.

“I’ve been the luckiest man on earth. I went from homelessness to governor of the state of Maine, and it’s my turn to give back, and it’s my way of trying to teach people how I did it,” LePage said. “For those who say it’s going to create poverty and hardship, let me tell you something. You don’t want to be poor. If you’re poor and you have the skills to get out, you will get out.”

No comments:

Post a Comment